Note: this is part of the twelfth edition of our weekly newsletter, the Databyte. To receive it in your inbox, subscribe here.

The last of the marathon of press conferences that FM Sitharaman held to announce the plan of the gigantic Rs. 20 lakh crore concluded today.

In case you missed it, it had everything from increased lending and changing the definition of MSMEs, power sector reforms and even a couple of space reforms.

Everything – except what people were hoping for and what most other countries have done – direct cash transfers.

In an interview with Barkha Dutt, Rajiv Bajaj summed up my thoughts perfectly. Speaking on direct cash transfer v/s the 20 lakh crores package, he said:

“As an engineer, this seedha-seedha economics (straightforward), I understand – you give money in the hands of the person or the employer.

As compared to this ghoom-firke stimulus (complex) which will come from here,

go there,

convert to this,

and then come to you,

in this way

at that point in time.

Perhaps it is my ignorance, but I do not understand this.

But, I cannot help but feel that something which is more simple, specific, direct and sustainable, would have been more meaningful.”

What could this simple, specific and sustainable measure be?

Universal Basic Income?

No. Too complicated to be implemented in such a short time. It’s also fraught with several issues apart from the fact that there’s no global example of a version of UBI working as yet. Finshots had this excellent primer recently.

Direct cash transfers? Employee retention schemes through furloughs?

Among all the announcements, there is little naya paisa that the government will spend of its own. It is as poor as the rest of us. But, this is a pet topic of my colleague John, and maybe we will coax him into writing one edition of the Databyte on this.

So, what can be done?

The government still has one instrument of wealth transfer that it can mobilise.

One that the current NDA dispensation despised when it came to power.

One that the Prime Minister considered to the headstone of UPA’s mis-governance.

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA)

MNREGA has 10 different problems. But at this point, it’s best suited to deal with the crisis.

Migrant workers are going back to their villages leaving their place of work. They no longer have jobs but have job cards. These job cards are linked to their bank accounts. MNREGA has the infrastructure to transfer payments directly to these bank accounts.

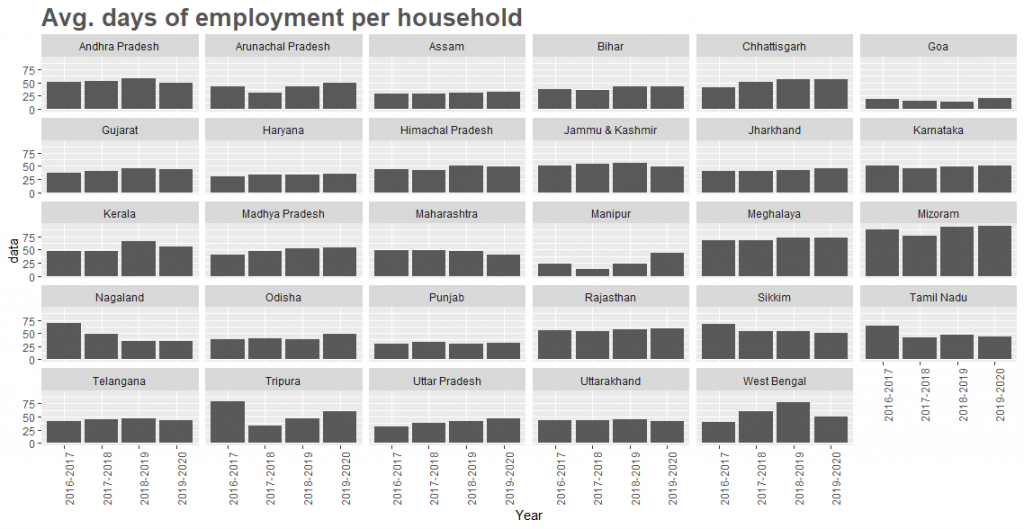

MGNREGA, launched in 2005 was envisaged as a provider of rural employment to casual workers at government-mandated minimum wages set above market wages.

In 2007-08, wages under MNREGA were 5% higher than rural wages for men and 50% higher for women. By 2009-10, wages were only 90% of the rural market wages and 26% higher for females. The UPA contributed to the weakening of the act by lowering allocations and introducing administrative bottlenecks in its second term. The NDA carried this forward.

However, once the rural distress started showing in the NDA’s second term, it has increased allocations and doubled down on the act.

Prior to the last financial year which saw close to a month being disrupted due to Covid-19, many states saw an increase in the average days of employment per household. The act mandates provision of 100 days of guaranteed wage employment to all rural households enrolled.

In the last episode of the Rs. 20 L crore stimulus package today, FM Sitharaman once again relied on MNREGA. It increased allocations from Rs. 61,000 crore to Rs. 100,000 crores. It also increased the minimum wages under MNREGA from Rs. 180 per day to Rs. 202 per day per worker.

There are additional talks of including factories and shops under the ambit of MNREGA given the additional demand expected. Wages under MNREGA will be over and above the wages that private enterprises pay. These are part of the suggestions that a Group of Ministers have submitted, and we do not know whether it will be implemented or whether these incentives are enough for private enterprises.

However, the loss of incomes for these rural workers is real and is felt. The lost 50 days will be acutely felt and MNREGA can be an effective tool for the government. Under the Act, there are provisions of increasing the mandated days to more than 100 days in times of adversity.

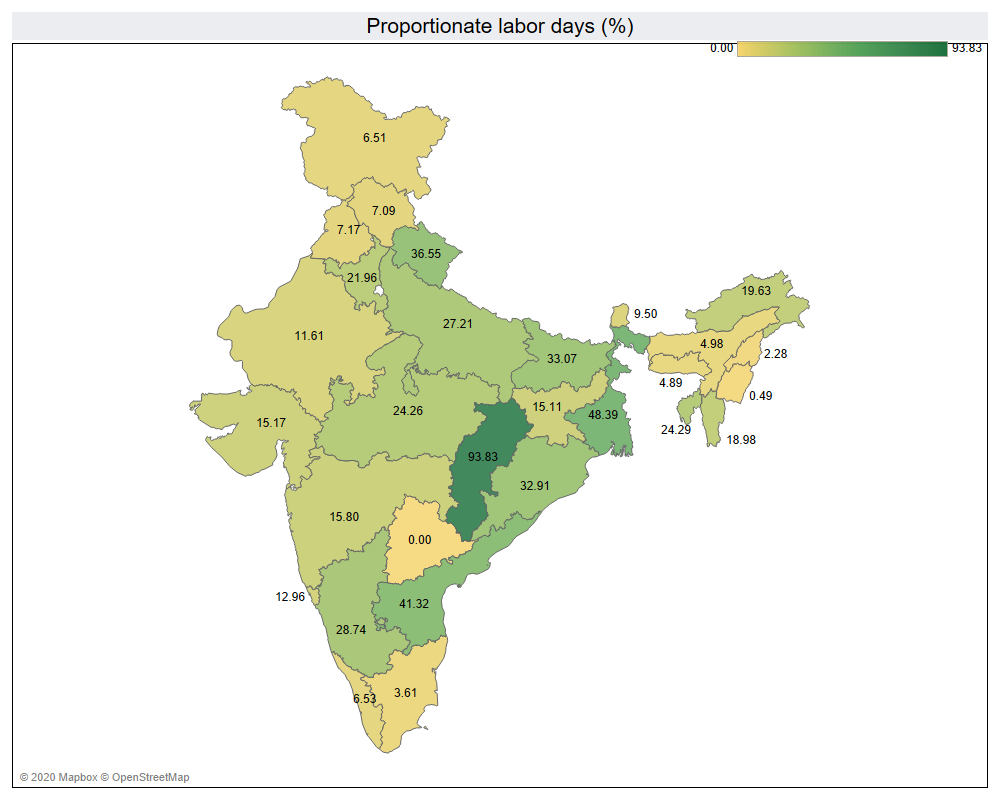

Apart from Chhattisgarh, all other states have seen a collapse in the number of labour days. For Southern states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, the share of proportionate labour days over last year is in single digits. Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir too could only generate 7% of labour days over last year.

Proportionate labour days is the share of labour days generated in the same time period over last year.

The Finance Minister said today that the aim was to generate 300 crores labour days of work to address the needs of the returning migrants. That’s 35 crores more labour days than 2018-19.

The body under the headstone is alive and kicking, and the NDA seems to have adopted it.

To get the Databyte in your inbox every Sunday, subscribe here.